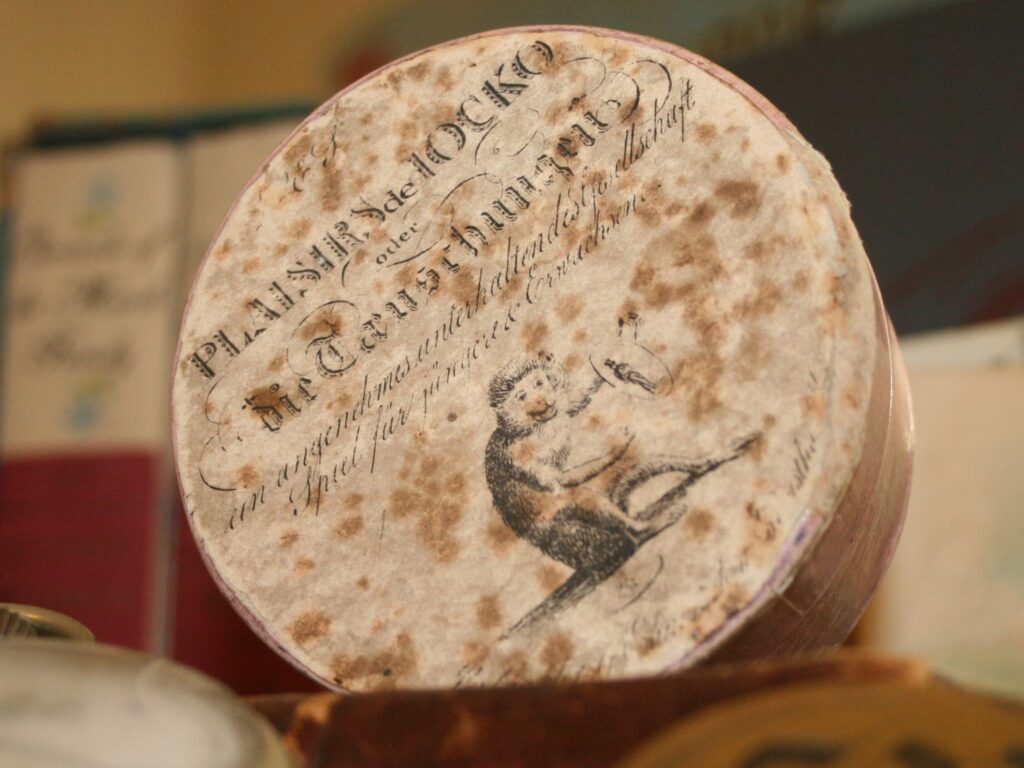

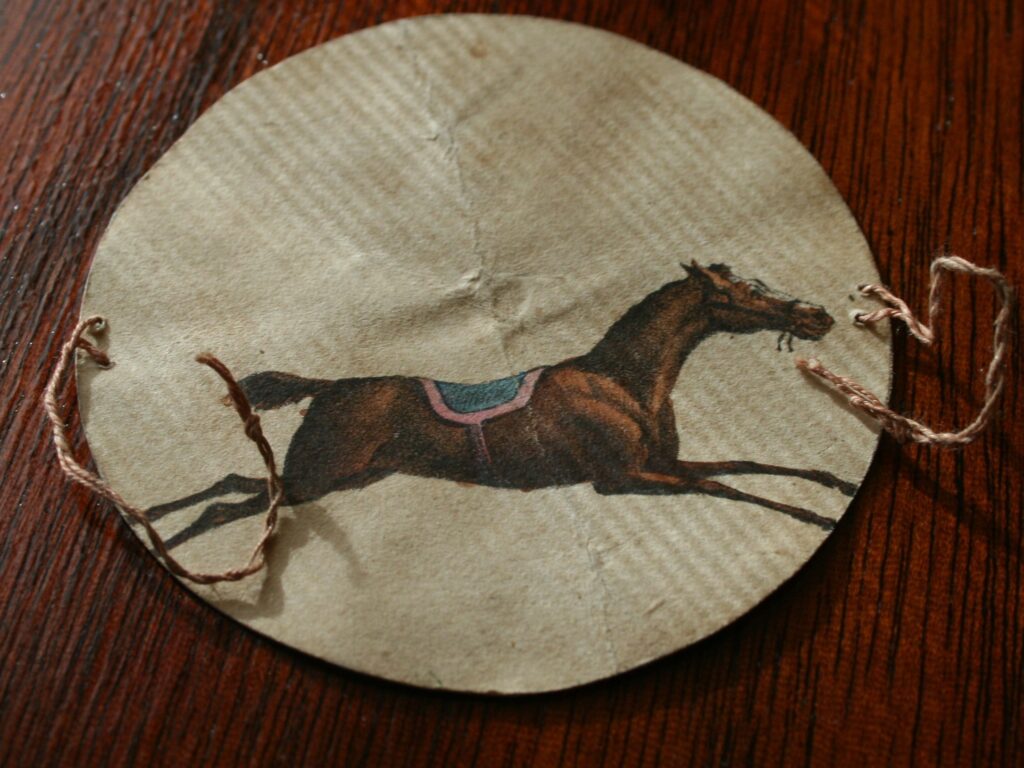

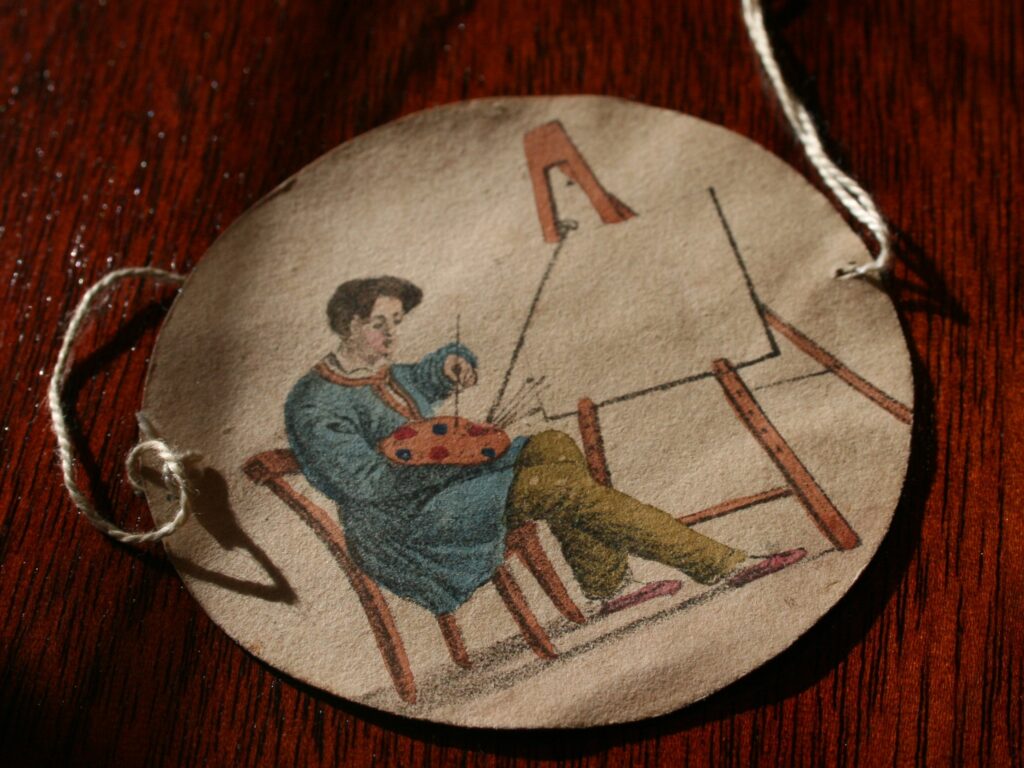

Exceptionally rare early thaumatrope collection. The set is complete with 24 discs housed in the publisher’s box. Each disc has hand-colored engravings and tied silk strings. Distributed on the cusps of the Georgian and Victorian eras by Alphonse Giroux, Paris, 7 rue du Coq Saint-Honoré. In remarkable antique condition with astonishingly vivid colors and all strings attached.

Subject Matter

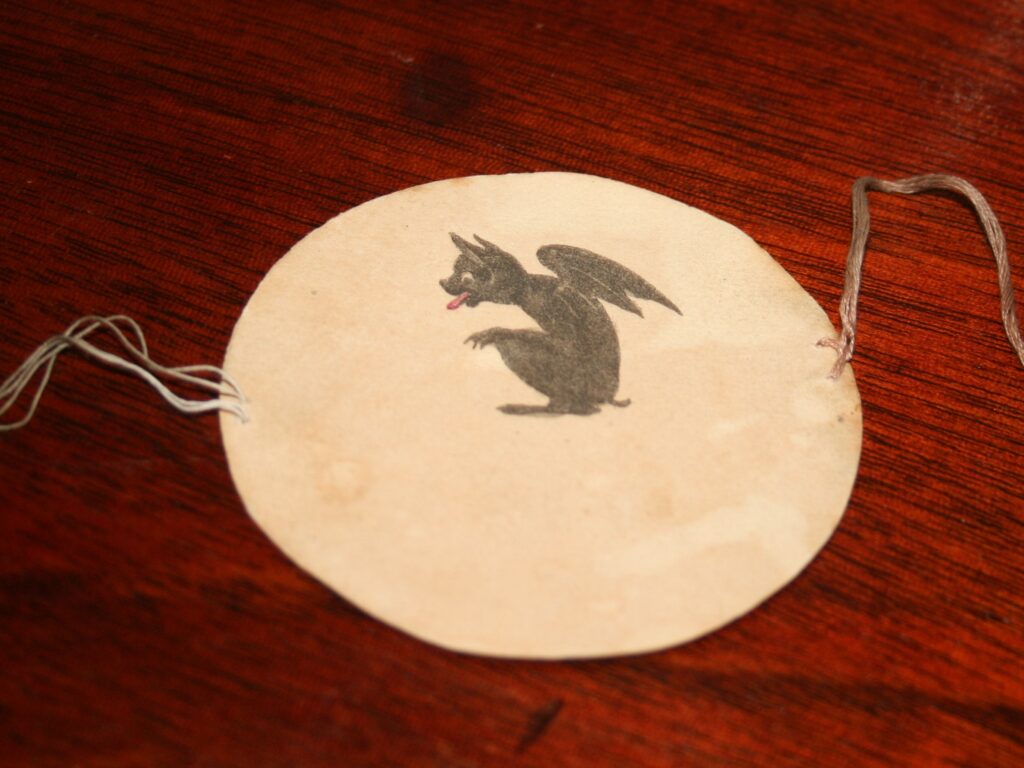

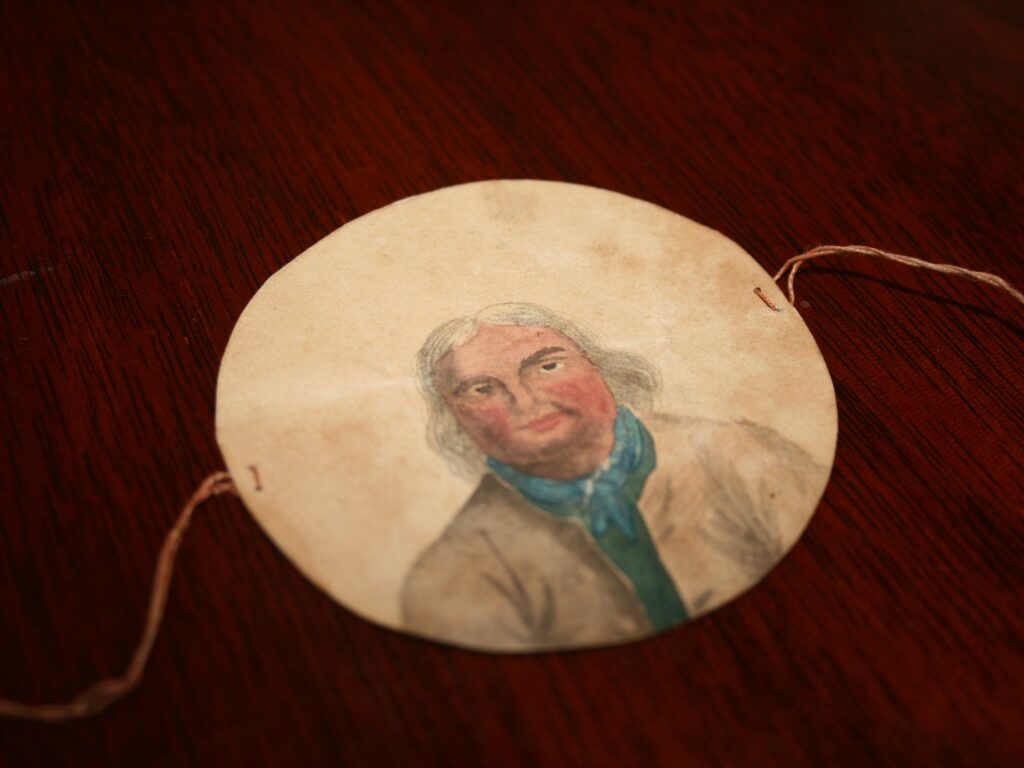

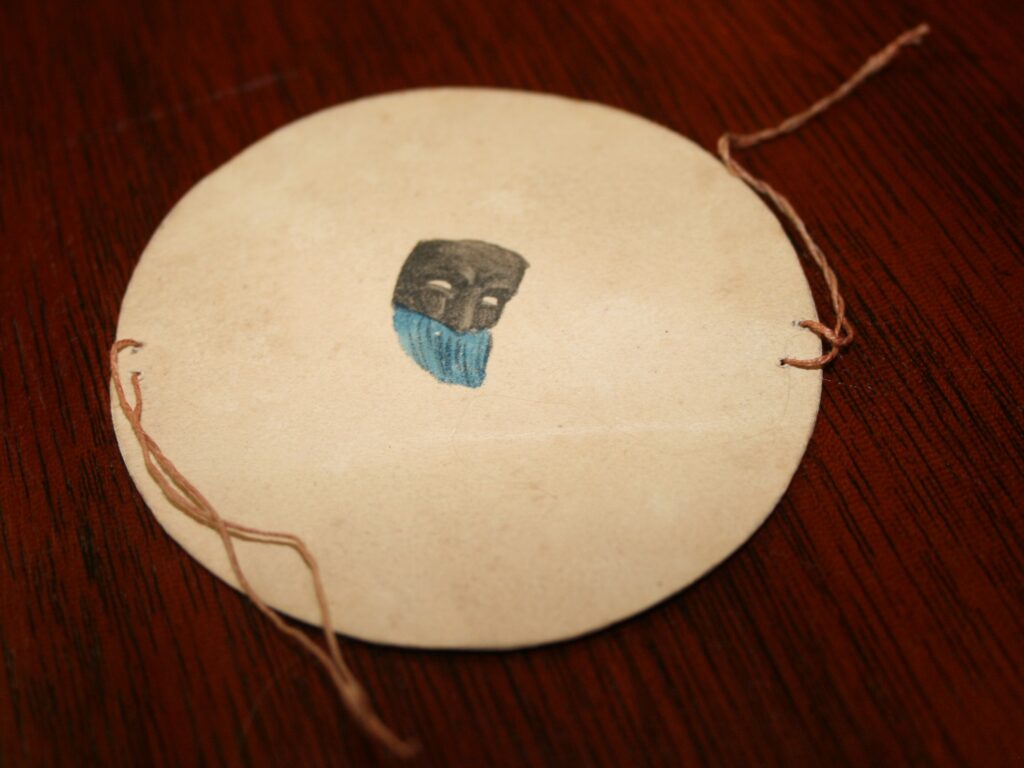

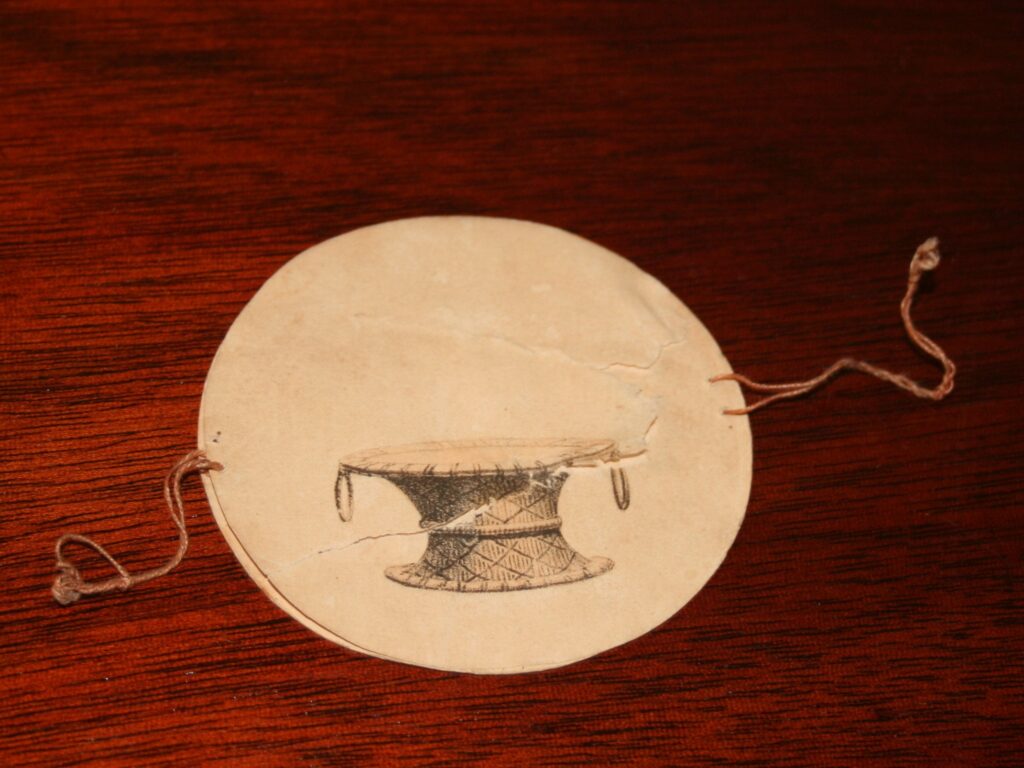

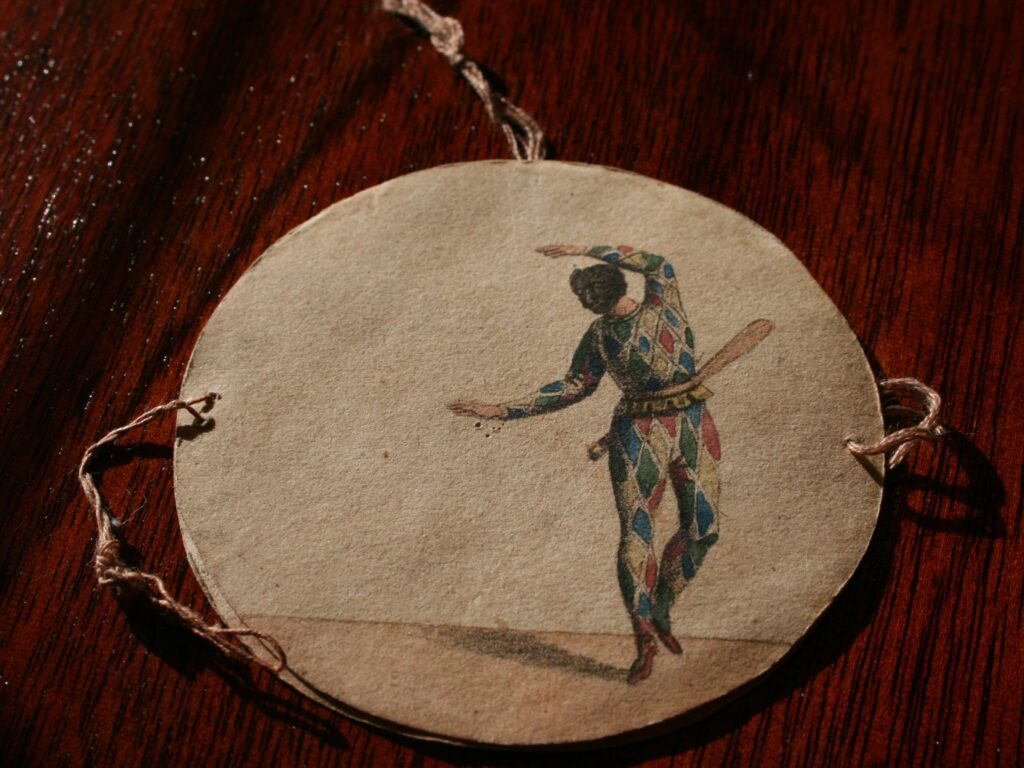

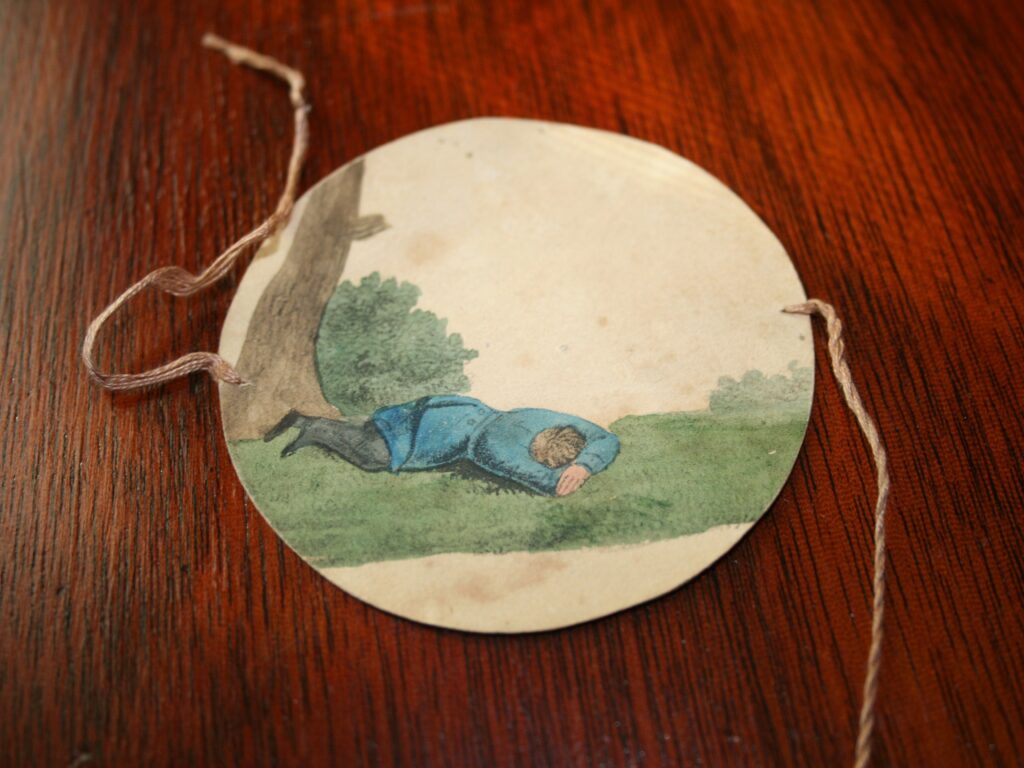

The collection includes an interpretation of Henry Fuseli’s painting “The Nightmare” (1782) with a woman in a vivid green gown, sleeping on a chaise, a demon perched upon her breast. Also, Harlequin (or Arlequin), the theatrical devil, is depicted dancing. (A reference to Armand d’Artois’ “folie-vaudeville” Le Sultan du Havre, and reminiscent of Charles Malo’s Almanach des Spectacles.) There is also a classic depiction of Napoleon and of Aesop’s vanity tale Fox and Crow. Represented fashions span eras and nationalities (see, for example, the courting couple in possibly Regency Era costume; masquerade lady; sword juggler; tightrope performer; mule driver; portrait painter). Sex, gender, and romance are especially showcased by a woman in a state of undress, and a monocled male gaze on a woman’s posterior. Other anthropological peeks at Victorian life include horticulture and playing cards. Care for a game of Whist or Commerce out in the garden?

Condition

There are scarce areas of damage, most notably a crack on the basketed floral arrangement, a crease in the trick-rider, and foxing on the box lid and the disc depicting Napoleon. Note: Thin lines appear across some of the photos, which do not indicate any damage. These are shadows in the image and are distinguishable from the light foxing observed on several cards.

approx. 7 x 7 x 3cm, 1.3oz

Scarcity

This is one of perhaps only two in existence. An identical edition is housed in the Princeton University Graphic Arts Collection. A dealer in Paris displays an incomplete set. An even earlier (1830) set (of 24) exists in the National Center for Cinema and the Moving Image in Paris collection.

Presumably, only two of the first sets ever issued have survived — a boxed set of 12, issued by Dr. John Paris in London in 1825. One existed in the private collection of the late Richard Balzar. Much of Balzar’s collection was bequeathed to The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures (USA); however, the object is not listed in their collection. The other is exhibited at the Art Museums of Colonial Williamsburg in Virginia.

Balzar also possessed an early American-issue thaumatrope collection (1840). That collection consists of 12 square cards and sadly lacks the box.

About Thaumatropes

From the Greek “thauma” (wonder) and “tropos” (to turn). Rolling the strings between the fingers spins the card rapidly, creating the optical illusion of merging two partial images on each side into one. (See the embedded demonstration video below.)

Sometimes called “Magic Circle” and “Rounds of Amusement,” it is an optical toy and juvenile science education device. It demonstrated what was thought of at the time as the phenomenon of persistence of vision. This understanding would lead to animation and cinema. The cards’ subjects included classical allusion and social satire, and often featured visual puns, providing a modern anthropological glimpse into Victorian humor.

Physician John Ayrton Paris presented the thaumatrope at the Royal College of Physicians in 1824 to demonstrate retinal persistence. The following year, he distributed them for sale as youth education ephemera.

Credit for the invention of the thaumatrope, however, remains disputed. In his autobiography, the “Father of the Computer,” Charles Babbage, recounts the following anecdote: At a party, attended by Dr. Paris, astronomer John Herschel, and Dr. William Henry Fitton, a spinning coin is presented by one or the other of them as a method by which the viewer may observe both sides of the coin at once.

Attributions have also been made to inventors William Hyde Wollaston and David Brewster.

Our understanding of the scientific principles demonstrated by the thaumatrope can be ascribed to the works of Aristotle, Leonardo da Vinci, Isaac Newton, Johannes Segner, Count Patrice D’Arcy, John Murray, and Peter Mark Roget. The thaumatrope would lead to the inventions of the anorthoscope, zoetrope, tachyscope, praxinoscope, and phenakistoscope, pedemascope in cinema history. And human fascination with movement illusion goes back at least as far as 30,000 years, as observed in the Chauvet cave paintings in France.

Resources:

Trompe-l’oeil ou les plaisirs de Jocko (1837) in the Princeton University Graphic Arts Collection

Trompe-l’oeil ou les plaisirs de Jocko (1830) in THE CINÉMATHÈQUE FRANÇAISE, National Center for Cinema and the Moving Image (CNC), Paris, France

Thaumatrope (1825): in the Bucknell University Digital Commons

Stephen Herbert: The Thaumatrope Revisited; or: “a roundabout way to turn’m green”

(Includes images from Dr. Paris’ first 1825 “Rounds of Amusement,” presumably donated to The Academy Museum of Motion Pictures by the estate of Richard Balzar.)

Princeton University: pre-cinema optical devices

NPR: Weekend Edition Saturday: Science: A Flicker Of Inspiration Brings Cave Drawings To Life

Special thanks to Stephen Herbert for his article, which largely informed the above description.

scarcity rating: 5

SOLD. Follow on socials to see what’s new!

“Very pleased with the set. Kind Regards,”

Martin

/

United Kingdom

★ ★ ★ ★ ★